How does the decryption of a simple cipher work?

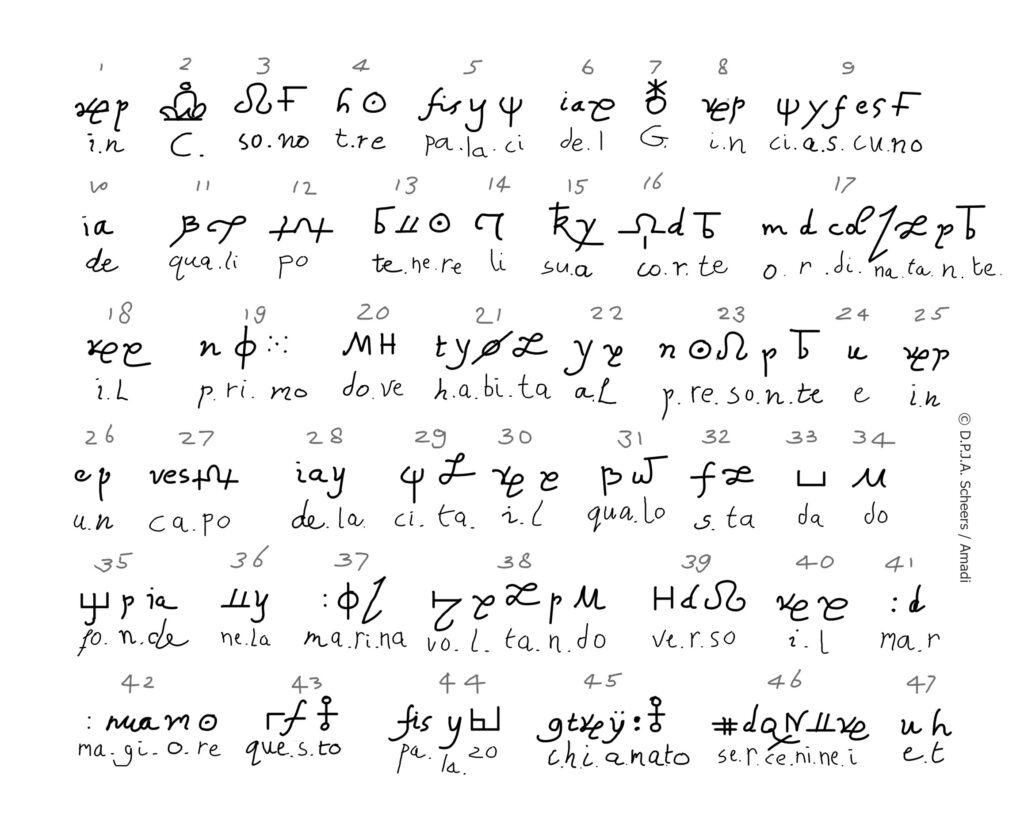

Here is a small explanation of the decryption of cipher in a video, this is from page 85r, volume 2:

The Second Volume On Ciphers and Decipherments by Agostino Amadi.

The second volume is the result of a transcription in the original Italian of Amadi’s second volume, where sometimes Latin is mixed with Venetian Italian and Spanish words in the handwritten text, which created some real challenges.

The entire text is then translated and although the original Italian text was completely transcribed, it is decided that only the English translation will be published at this point.

Available as:

eBook:

US: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0C6B2RRBL

UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B0C6B2RRBL

DE: https://www.amazon.de/dp/B0C6B2RRBL

Paperback:

US: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0C6BR8H5F

UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B0C6BR8H5F

DE: https://www.amazon.de/dp/B0C6BR8H5F

Hardcover:

US: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0C6C65JM5

UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B0C6C65JM5

DE: https://www.amazon.de/dp/B0C6C65JM5

Contents

The second volume discusses the decryption of the following 18 cipher examples:

-

-

- 163-81r: transposition cipher

- 166-82v: veiled cipher

- 167-83r: 2nd veiled cipher

- 168-83v: line cipher

- 170-84v: superfluous cipher

- 171-85r: symbol cipher

- 180-89v: second foreign cipher

- 186-92v: cipher with superfluous characters

- 205-102r: 12-letter cipher

- 210-104v: cipher with 20 symbols

- 217-108r: cipher with 3 alphabets

- 226-112v: Oedipus cipher

- 227-113r: transposition cipher

- 232-115v: Ticiano cipher

- 234-116v: queen cipher

- 256-127v: babuini cipher

- 268-133v: babuini cipher with squares

- 281-140r: the Spanish cipher

-

All cipher names, such as ‘Ticiano cipher’ are added by me for reference purposes and not by Amadi.

Amadi also explains the use of ‘babuini’ and shows use such ciphers and the solution with the ‘babuini’ tables:

-

-

-

- 240-119v: babuini rules

- 241-120r: 3-letter babuini: consonant + vowel + vowel

- 242-120v: 3-letter babuini: consonant + vowel + consonant

- 244-121v: 2-letter babuini: consonant + vowel

- 246-122v: 3-letter babuini: vowel + babuini + vowel

- 248-123v: 4-letters: 2 babuini

-

-

The Amadi manuscript mentioned by others

The original manuscript of Agostino Amadi was often referred to as ‘trattato delle cifre d’Agostino Amadi’ or

Agostino Amadi. Trattato delle cifre. 1588. Trattato delle cifre. Venezia.

Ciphers of Agostino Amadi, 1588 in the Archivio di Stato di Venezia.

Some historical remarks and references to the manuscript are summarized. Those that were already mentioned in Volume 1 are omitted and only new references are shown here.

Aloys Meister [1]

Meister was a German historian and studied theology and history before he became a professor and organized the history of cryptology in extensive works. During his life in the years 1866-1925 he examined especially ciphers in the medieval period in Europe with the main focus on the Italian Archives. He writes: [2]

In addition, the Archive in Venice keeps holds three treatises on ciphers from the 16th century, the exact date of which I could not determine during my stay, that are in the Venetian Archive in a box called busta VI ‘trattati in cifra etc.’, in quarto the numbers 5,6 and 7.

The latter, number 7, is a fragment of a treatise that was supposed to have seven sections and is probably related to the tract by Agostino Amadi to be mentioned hereafter. This treatise by Agostino Amadi, dated March 6, 1588, is the most important and richest one that the Venetian state archive has today.

It contains 10 volumes; the first one shows the different kinds of cryptography; the second one explains foreign and unknown ciphers; the third is called by Armadi ‘Polistenographia’ and the title shows that it deals with ‘zifre non suspete ne conosute per zifre’; the fourth is entitled ‘Apocriptogafia’; the fifth deals with invisible writing; the sixth seems originally to be meant as the end, it is called ‘ultimo volume de le zifre cioe la somma d’Agostino Armadi‘.

It is followed by a part in paper appended to the parchment codex, namely a seventh book with examples, keys and rules by Armadi; the eighth book contains 76 ciphered examples; the ninth has explanations for the preceding ciphers, and finally a tenth that also contains various cipher examples. The Council of X has shown its appreciation to Armadi in recognition of his merits and admitted his two sons to the Secretaries and awarded them also lifelong salary of 109 ducats a month.

David Kahn

Writes in his popular book on ciphers on page 110:

“That by Soro, written in the early 1500s on the solution of Latin, Italian, Spanish, and French ciphers, is another Lost Book of cryptology, for though he turned it over to the Council of Ten on March 29, 1539, no trace of it can be found in the archives. Fragmentary notes written by his successor, Giovanni Battista de Ludovicis, survive, and so do careful thorough surveys of the field by other cipher secretaries, Girolamo Franceschi, Giovanni Francesco Marin, and Agostino Amadi, whose manual is especially fine and whose work was so outstanding that Venice rewarded him by giving his two sons pensions of ten ducats month for life. The Council of Ten held contests in ciphers, and advances in the art were rewarded: a Marco Rafael, later a favorite of Henry VIII of England, received 100 ducats in 1525 for a new method of invisible writing. If the cipher secretaries made valuable suggestions, they would get a raise. On the other hand, if they betrayed any of the state cryptologic secrets, they could be put to death. The council was as alert to protect its own ciphers as it was to solve those of its rivals. It kept a number of nomenclators ready to replace compromised ones, and it did not hesitate to use them …”

Michel Hochmann

He is specialized in Renaissance Venetian art and investigates the relationship between painters and their patrons in Venice during the 16th cent. and studies the history of collections and painting techniques. He wrote in the article “A visit to Titian’s studio” the following:

“Agostino Amadi, who died in 1588, was a very unusual character whose life in Renaissance Venice has not received the attention it deserves. He belonged to the class of ‘cittadini originari’, an intermediate class to which the duties of secretary to the various public offices in Venice were entrusted. Amadi himself was employed as secretary to the Council of Ten: although he did not exercise direct power – this was reserved for the nobility – he nevertheless belonged to a group of public servants who often wielded considerable influence over affairs of state. Agostino was highly cultivated: he knew Greek, Latin, and Hebrew.”

… This is a superb manuscript written on paper and vellum, decorated with diagrams and wheels, some of which can still be turned today.” [3]

Luigi Pasini

He mentions the manuscript [4] when he writes that the Doge of Venice from 1585 to 1595, Pasquale Cicogna (1509-1595) sighed: [5]

“The investigations I made to find this work in the General Archives were fruitless.

There was no doubt, being mentioned in a List of Archive Codes copied by Rossi in volume XII

of the documents of his unpublished work … various treatises and different specimens of ciphers by Agostino Amadi 1588 in 4° covered with Moroccan.”

The article ‘Deciphering Galileo: Communication and Secrecy’, by Hannah Marcus, Paula Findlen:

“…Galileo’s experiences in the Venetian Republic made him aware, as Agostino Amadi wrote in 1588, that ciphers were not only for princes to hide state secrets, clerics to obscure divine mysteries, and lovers to communicate their passion in private, but they were also useful for learned men eager to keep their best ideas, discoveries, and inventions hidden. Amadi firmly connected cryptology and mathematics by insisting that no one could write or break decent code without “true knowledge of algebra.”

[1] Meister2 p.24

[2] Translated from German, “Außerdem bewahrt das Archiv zu Venedig noch drei Abhandlungen über Chiffren etc…“.

[3] See the reference list Hochmann. He also mentions: Amadi’s biography by: F. Pitacco, in M. Hochmann, R. Lauber and S. Mason: Il collezionismo d’arte a Venezia. Dalle origitii al Cinquecento, Venice 2008, pp.250.

[4] The translation is called Written Ciphers Used By The Republic Of Venice, Luigi Pasini, 1872, translated 2021.

[5] In “Delle Inscrizioni Veneziane”, Vol. VI, p. 382. Also mentioned by Pasini p.42. See references.

Some images in the book in the additional comments are in full colour.

Because the book as paperback and as hardcover are printed in black & white, those images are omitted from those editions and the images are given here additionally.

– click on the images for enlargement-

167-83r: 2nd veiled cipher

The letters analysed in the ’words’ of both the cipher in the left graph, as well as the plain text solution, in the right graph, of the 82v cipher are shown here in their word-positions.

It the left graph of the cipher the placement of the vowels e.a.i and o. at the end (z-pos) of words is very obvious.

The right graph shows the graph of the plain (deciphered) text.

Notice that smaller words such as te.de.ne. have the letter e. on the 2nd position; in the plain text they become et.ne.de.

For a further explanation of the graphs, I refer to the appendices.

204-101v: solution of the superfluous cipher

It is interesting to see in the cipher how words at the end of the line have been split up. Notice the clever distribution of the nulls, visible in the following transcription:

Based on the graph one could immediately see that the only characters that are used as word-finals are the 7,5,6,2,1,3,4 and a little bit the i,r,L,S. From that we can conclude it is no coincidence that superfluous characters are dominantly found at word endings, which has been mentioned by Amadi for this cipher on pages 95r and 97v.

But as you can see, they are also at other positions, or like 6, not on A-pos, but on B-pos.

209-104r: solution 12-letter cipher

The graph below shows the decrypted letters, and their relative position in the words:

For the displayed graph the lines have been used where the words with line-endings have been merged with words on the next line. Clearly the c, t and the s are never at the end of a word.

Notice that the frequency is quite different than that of the Italian language from 1649. Especially for the letters t: n:u:c: and L: if we look at the percentages.

In the table on the left the frequency of this cipher is compared with Italian on the right.

217-108r: solution, cipher with 3 alphabets

The cipher alphabet with the homophones, the multiple symbols for the vowels, has been analysed, so we can see what effect it has on the distribution, using it with the following assignments:

The transcription took some time, but this enables us to compare the text that starts with ‘ess2nt4 t3m1ntat8 6 s7i4ne cu/2Lo c2 3 re e rinc37 15es3n8 t7…’ with the standard Italian frequencies.

The frequencies of the transcript a=1=6, e=2, i=3=7, o=4=8 and u=5, shows that these homophones are scattered throughout the frequency-list and based on them it is almost impossible to extract them based on the frequencies alone.

Even the letter c: with such a high amount doesn’t help us, and that is caused by the fact that the counts of symbol 2: and e: must be added in order to get almost 13%. The homophones that jump out for me are the 1: and 5: because the 1: is always at the word beginning and the 5: seems to be dominant more at the second position.

With these symbol counts we could make 380 combinations (20×20-20) and then try those in combination with the 21 plausible letters of the Italian alphabet and try them on the two and three letter words, or on the trigraphs with the highest frequencies, or use the specific words that Amadi suggests.

To complete a raw analysis here, there is also a graph for the final 108r text, so the text “Essendo dimandato…”.

Looking at the word-final characters, or the Z-pos, it can be seen that there are only 6 for that position. In descending order: letters i: o: e: and n: a: and finally, the letter r. Other characters do not appear as word final.

223-111r: solution

Comments:

The text from the cipher example appears to come from ‘Della imitatione poetica’, by Bernardinus Partenio, Vol. 6, Libro Primo. 1560. Remarkably, the last words of the text are quite different in their decrypted text from the original because the text from the book ends like this: ‘…et misurandole con la Poesia, non solamente a ciascuna di quelle l’agguaglio’. But the decrypted text of the cipher here is: ‘Ma come che queste arti siano state et siano di tanto ornamento, non dimeno considerando queste discipline et misurandole con la scientia delle zifre questa apresso di esse la paregio et agualgio.’

Translated: ’ … but as these arts have been here, and still are, much more than only an ornament, we must consider and measure these disciplines within the science of the ciphers with balance and equivalence’.

First, on pages 109 and beyond, we’re investigating several different letter arrangements, such as counting the occurrences of a vowel-consonant, symbols-numbers and similar, numbers and letters, letters and symbols and other combinations. This process seems useful for finding the typical decipherment alphabet.

Then by using the small words we find out the possible vowels and then in combination with some logic the first letters are found. From there, everything reveals itself easily once discovered that the letters simply must be shifted one position backwards on the alphabet to reveal the plain letter.

The graph below shows the 26 lines of the decrypted plain text, using the original line breaks:

First, a transcript was made for the entire cipher, where numbers and letters are used for the symbols. You can see that the 3 alphabets together do not provide clear clues to the final deciphered letters, primarily because of the multitude of the symbols and their spread.

Letter frequencies

If the frequency of the final deciphered plaintext is compared with that of the Italian letter frequency, you can see that the percentages and the positions in the list are different for almost every letter. This shows that one has to take into considerations that the statistics of a small, ciphered letter could be quite different than the average percentages.

231-115r: solution

An analysis of the letter frequency and of the words was done:

255-127r: solution

Some analysis of the cipher solution text shows the following: (the nomenclators have been replaced by G and C):

The cipher.

Looking at the cipher itself, that is before the solution is known which is used for the graph, we notice that the cipher-words are very small, on average two and a half symbol, and the longest cipher word is only 7 long. Knowing that the average word-length must be around 6 letters, we then already know that the 2 or 3 symbols must refer to something more than just one letter.

In total we count 61 different symbols that are used, we see that they can be divided in 14 single letters (including the G. and C. and p: and h:) and 47 babuini. That quantity is the second reason that shows us that the symbols must be syllables or a whole word. Thirdly, looking at the letter-word contacts there are no reasons to assume that any symbol is a duplicate of another based on this small text, this can be seen in the graph as well when we look at the letter positions in the words and see that they are scattered.

In the cipher the words in: e: il: are repeated the most overall with 4, 4 and 3 repeats.

267-133r: babuini table

…

The babuini table is missing several babuini that are definitely used in the cipher. I’ve added the following: ce: in word 26, fe: in word 68, ve: in word 62, zi: in word 89, no: in word 69 and others, qua: in word 1 and others.

If we take all the 47 babuini and make a letter-word graph as below, it will resemble the graph I’ve made for 116v.

278-138v

…

Analysis

Only the square/pigpen-like symbols are separate letters, all the others are babuini. The last symbol on the first line is either a mistake or a deliberate null character. Again, every babuino always begins with a consonant and ends with a vowel, and except the qua and que every babuino is only two letters. This implies that every word that starts with a vowel or with two consonants, such as ‘in’ and ‘che’, is easy to locate, even more because these words occur both 5 times in this text.

Appendix: Language frequency Italian

..

The letter positions and their counts are in the following graph. If we consider looking at words separated by a space and a word in a sentence is presented as ABCdXYZ. Then the letter A is in the first position and the Z in the last.

For Italian can be seen that as word-final letter, the Z-position, the most occurrences can be counted for e,i,o,a and a little bit for L,r and n.

Very rarely the vowel u is word-final. The other vowels are very often word-final, in fact they are the most word-final letters. Especially the ò. Word-initial is very rare for the vowel o: and u:.

Appendix: Language frequency Spanish

..

For more information please consult the published information.